Migration Missive: Dispatches from the Migrant Road

Diocesan Migration Missioner Troy Elder writes with updates from his weeklong journey through Guatemala and southern Mexico as a guest of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles and the Anglican Diocese of Guatemala. Troy can be reached at telder@edsd.org.

Day 1: At Long Last, Headed South

It was hard to believe this day had finally come. After nearly two years and several pandemic-related postponements, I was finally headed to LAX to join other Southern California Episcopalians for a week of pilgrimage, accompaniment, factfinding, and witness along the “migrant road”—a route commonly taken by people from around the world who have been forcibly displaced by violence, environmental disaster, extreme poverty, and racism. Our small group included clergy, laity, and diocesan staff, most of whom were seasoned church immigration activists who had been to the region before. The purpose of our visit to Guatemala and, later in the week, to Tapachula, Mexico was to strengthen ties with partners in both countries while learning more about the personal narratives of those who set out on the migrant road. Upon our return, we hoped to deepen our fellow Episcopalians’ understanding of the human dimensions of the crisis and become more effective advocates for Christ-centered U.S. policies.

It was hard to believe this day had finally come. After nearly two years and several pandemic-related postponements, I was finally headed to LAX to join other Southern California Episcopalians for a week of pilgrimage, accompaniment, factfinding, and witness along the “migrant road”—a route commonly taken by people from around the world who have been forcibly displaced by violence, environmental disaster, extreme poverty, and racism. Our small group included clergy, laity, and diocesan staff, most of whom were seasoned church immigration activists who had been to the region before. The purpose of our visit to Guatemala and, later in the week, to Tapachula, Mexico was to strengthen ties with partners in both countries while learning more about the personal narratives of those who set out on the migrant road. Upon our return, we hoped to deepen our fellow Episcopalians’ understanding of the human dimensions of the crisis and become more effective advocates for Christ-centered U.S. policies.

Day 2: What a God-“incidence”!

Our redeye flight landed in Guatemala City in time for breakfast with the Rt. Rev. Silvestre Romero, the Bishop Diocesan of the Anglican Diocese of Guatemala, and our host, guide, driver, and spiritual and emotional leader for the visit. Affable, erudite, humble, and deeply spiritual, Bishop Silvestre shared with us that he had long hoped for an occasion that might catalyze concerted action among the Anglican/Episcopal dioceses of Central America and Mexico around migration. Underscoring that objective, for our first day, the Bishop had convened several of his clergy, seminarians, and laity to meet with us. The venue was as spectacular as it was spiritual: a nearly 500-year-old former convent, the Convento de la Concepción, an architectural jewel in Antigua Guatemala, the country’s colonial capital. Coming from various regions of the country, the small group represented Guatemala’s indigenous, colonial, and modern past, all of which have been affected by migration. (When it turned out that some of the local group already had some connections with those of us visiting, we noted the coincidence—which Bishop Silvestre quickly reminded us was, rather, a “God”-incidence!)

Day 3: Ambassadors of Different Sorts

Our third day began with a visit to one of Guatemala City’s migrant shelters, the Casa del Migrante. Run by the Scalabrinians, an international religious order that serves migrants and refugees, the shelter forms part of a network of ministries in cities in 32 countries, including in Tijuana, just a few miles from our Diocese. We learned that, hours earlier, a caravan of migrants had left Guatemala City for points north. We asked the shelter psychologist if the migrants were aware of the many dangers posed by the journey, including extortion and violence at the hands of cartels, gangs, and Mexican police; extreme conditions of heat and cold; and pervasive anti-migrant sentiment along the way. With a gentle sigh of resignation, she explained that the poverty, violence, and environmental degradation that the migrants were fleeing far out shadowed the perils of the road: “As they often say, ‘might as well die on the way, we’re as good as dead if we stay home.’”

Our third day began with a visit to one of Guatemala City’s migrant shelters, the Casa del Migrante. Run by the Scalabrinians, an international religious order that serves migrants and refugees, the shelter forms part of a network of ministries in cities in 32 countries, including in Tijuana, just a few miles from our Diocese. We learned that, hours earlier, a caravan of migrants had left Guatemala City for points north. We asked the shelter psychologist if the migrants were aware of the many dangers posed by the journey, including extortion and violence at the hands of cartels, gangs, and Mexican police; extreme conditions of heat and cold; and pervasive anti-migrant sentiment along the way. With a gentle sigh of resignation, she explained that the poverty, violence, and environmental degradation that the migrants were fleeing far out shadowed the perils of the road: “As they often say, ‘might as well die on the way, we’re as good as dead if we stay home.’”

Later that afternoon, we were received by William Popp, the U.S. Ambassador to Guatemala, at the ambassador’s residence. A career diplomat with extensive experience in Latin America and elsewhere, the Ambassador seemed most at ease when discussing long-term economic development in Guatemala as the solution to the woes of forced migration. When confronted with the urgency presented by the human suffering along the migrant road, however, he did seem supportive of expanding existing visas to enable legal migration. When prompted, he also seemed to acknowledge a role for communities of faith in expanding access to such avenues. We took his card and promised to follow up, and we will.

Day 4: The Least of These

Vuln erabilities of all sorts—including ours –surfaced on Wednesday. One of our intentions for the trip was to lift up stories of groups whose migratory paths were particularly difficult, such as those of children, Black people, and LGBTQ migrants. We began our day speaking with Alan Yarborough, with The Episcopal Church’s Office of Government Relations. His portfolio of projects includes Haiti, and the plight of Haitians at the U.S.-Mexico border and at our next destination, Tapachula, in southern Mexico, has made international headlines. Next, we visited with LGBTQ advocates and activists at Cristosal, a Central American human rights organization with deep Episcopal roots. We rounded out the day with a meeting with the director of an educational program for child workers in Guatemalan marketplaces.

erabilities of all sorts—including ours –surfaced on Wednesday. One of our intentions for the trip was to lift up stories of groups whose migratory paths were particularly difficult, such as those of children, Black people, and LGBTQ migrants. We began our day speaking with Alan Yarborough, with The Episcopal Church’s Office of Government Relations. His portfolio of projects includes Haiti, and the plight of Haitians at the U.S.-Mexico border and at our next destination, Tapachula, in southern Mexico, has made international headlines. Next, we visited with LGBTQ advocates and activists at Cristosal, a Central American human rights organization with deep Episcopal roots. We rounded out the day with a meeting with the director of an educational program for child workers in Guatemalan marketplaces.

As was perhaps fitting, that evening we ended our stay in the Guatemalan capital with a period of repose, prayer, and community, coming together once again with our Guatemalan brothers and sisters for an evening study of the Book of Exodus. Recounting the most famous migration in history, the Exodus account of the journey of the Israelites from slavery to freedom provided a poignant reminder of God’s enduring commitment to those forcibly displaced.

Day 5: Continental Divide: A very “un-porous” border

On Thursday, we hit the road. In our small “busito” (van), we drove northwest from Guatemala City through a varied and often spectacular countryside of volcanoes, coffee fields, and villages. Although much of what we traversed was technically rainforest, due to a harvest-destroying, historic drought, it was now part of the “Dry Corridor,” a swath of Central America that has punished subsistence farmers, contributed to a growing famine in the region, and propelled migrants north.

On Thursday, we hit the road. In our small “busito” (van), we drove northwest from Guatemala City through a varied and often spectacular countryside of volcanoes, coffee fields, and villages. Although much of what we traversed was technically rainforest, due to a harvest-destroying, historic drought, it was now part of the “Dry Corridor,” a swath of Central America that has punished subsistence farmers, contributed to a growing famine in the region, and propelled migrants north.

As we approached Guatemala’s border with Mexico, near the Suchiate River and where North America and Central America meet, those of us who had visited the region a few years earlier were struck by the tight (and lengthy) border checkpoint. Back then, in 2017, crossing the border (in either direction) meant shuttling back and forth across the shallow, muddy river on a makeshift raft made up of shipping pallets and truck inner tubes, with no immigration or customs controls in sight. Today, a few miles upriver, our checkpoint consisted of an hourlong wait, immigration control, and multiple luggage checks. As we waited, large buses idled on the Guatemala side of the border, at the ready to return migrants who had been intercepted by the United States and Mexico to Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. As we were to learn, the pact between these countries had, in effect, externalized the U.S. border, pushing it some 2,400 miles to the southeast of Tijuana.

Day 6: Tapachula: The open-air “prison city”

Friday dawned hot and humid in Tapachula, a southern Mexican city that has in recent years served as transit point, bottleneck, and de facto prison for thousands of mostly Haitian migrants who have been stranded here—the Mexican government until quite recently having denied them permission to move north. We first met with activists and advocates from the LA-based Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, who had been stationed in Tapachula for several years. We visited the Mexican asylum office, next door to the United Nations refugee agency, where scores of migrants, mostly Haitian, waited outside to be called for interviews. Nearby, in a repurposed train station, we visited a medical clinic that served migrants and a Mexican-government sponsored artisanal craft shop where migrants sold goods. Later in the day, we visited a shiny new UN-funded migrant shelter that housed people applying for asylum in Mexico (but not those making journey further north)–a further, bricks-and-mortar sign of the normalization of the externalization of the border.

Friday dawned hot and humid in Tapachula, a southern Mexican city that has in recent years served as transit point, bottleneck, and de facto prison for thousands of mostly Haitian migrants who have been stranded here—the Mexican government until quite recently having denied them permission to move north. We first met with activists and advocates from the LA-based Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, who had been stationed in Tapachula for several years. We visited the Mexican asylum office, next door to the United Nations refugee agency, where scores of migrants, mostly Haitian, waited outside to be called for interviews. Nearby, in a repurposed train station, we visited a medical clinic that served migrants and a Mexican-government sponsored artisanal craft shop where migrants sold goods. Later in the day, we visited a shiny new UN-funded migrant shelter that housed people applying for asylum in Mexico (but not those making journey further north)–a further, bricks-and-mortar sign of the normalization of the externalization of the border.

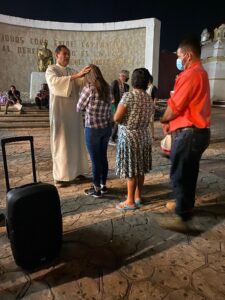

That evening we were joined by Julio Cesar Martin, Bishop of the Southeast Diocese of Mexico, which encompasses Tapachula. Led by Bishops Martin and Romero, we headed for the town’s central square, which was abuzz with activity of all sorts: migrants and others talking, laughing, selling, waiting. After setting up a portable speaker and handing out worship sheets to the curious onlookers, we celebrated a service of solidarity and thanksgiving for migrants. The clergy with us closed the service by offering blessings to the crowd.

Day 7: Hope: Moving forward with our partners in Christ

On our final day, the group reconnected with two longtime partners, El Buen Pastor and Todo Por Ellos, grassroots migrant shelters run on shoestring budgets that provided a stark contrast (in philosophy, capacity, and population) with the “official” UN-funded shelter. Run by activists with deep roots in the local community, these places house migrants in transit—which are the vast majority—as opposed to those electing to seek asylum in Mexico. With a capacity of 300, for example, El Buen Pastor was serving some 1200 migrants a day, evidence of the migratory “pull” of the United States, where demand for labor and, for so many, the promise of safety, outweigh asylum in Mexico, which in many cases can provide neither.

On our final day, the group reconnected with two longtime partners, El Buen Pastor and Todo Por Ellos, grassroots migrant shelters run on shoestring budgets that provided a stark contrast (in philosophy, capacity, and population) with the “official” UN-funded shelter. Run by activists with deep roots in the local community, these places house migrants in transit—which are the vast majority—as opposed to those electing to seek asylum in Mexico. With a capacity of 300, for example, El Buen Pastor was serving some 1200 migrants a day, evidence of the migratory “pull” of the United States, where demand for labor and, for so many, the promise of safety, outweigh asylum in Mexico, which in many cases can provide neither.

As was perhaps fitting, I ended my own trip north with a stopover in Guadalajara to visit The Rt. Rev. Ricardo Osnaya Gomez, the Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Western Mexico, a companion diocese to the Diocese of San Diego. Bishop Osnaya’s sprawling diocese encompasses 12 Mexican states, stretching across much of the western half of the country up to Baja California in the north, where it abuts ours. We discussed our current and hoped-for ministries in Tijuana, Mexicali, and elsewhere along our long mutual border. Plans were furthered for a visit by our Bishop Susan to Tijuana in the coming months. Bishop Ricardo was also eager to hear of the work of St. Margaret’s, Palm Desert, and St. Paul in the Desert, Palm Springs, at the La Cobina migrant shelter in Mexicali, where our clergy are now authorized to celebrate Eucharist, give blessings, and perform baptisms. A fitting coda to a rich, exhausting, but promising week, connecting with our longtime neighbor and border partner left me energized for the mutual road ahead.

To learn more about our Diocesan migration ministry, please contact our Migration Missioner, Troy Elder, at telder@edsd.org.

by

Category: #Advocacy, #Migration

Respond to this:

4 replies to “Migration Missive: Dispatches from the Migrant Road”

Recent Stories

My mother was ordained an Episcopal priest on January 15, 1994, at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Beverly Hills. I was ten years old, and her being ordained wasn’t odd […]

In December 2023, I received a letter from Julia Ayala Harris, President of the House of Deputies, saying, “I have reviewed your application and, after prayerful discernment, invite you to […]

When we love something, we share it with our friends and family; like a new show on Netflix or a great restaurant in the neighborhood, we can’t help but share […]

Troy, This is a much needed program, to understand the difficulties and challenges that the migrants face in coming to a better home. Hopefully the new Vice President and her attention to and for these people will be addressed with more compassion than previously. Thank you for caring enough to envolve the Diocese in this important work. Steve

Thanks very much, Troy, for your fine writing: making me feel as if I were by your side throughout the visit.

I look forward to your thoughts on how some of what you experienced could serve our diocese to better understand/respond to our sisters and brother refugees — something I experienced at age eight when our family

came to the USA as displaced persons in WW II.

I thank you for the report. I wish I could have been along. I was privileged to work alongside Bishop Romero on the diocesan staff at El Camino Real before he became bishop of Belize and now, Guatemala, and was present when his son was ordained to the priesthood.

On another note, I sent your previous report to a friend who works for Homeland security in Calexico. They were enthusiastic about your presentation. I will forward this as well.

Hopefully we are learning more ways to reach out during this fraught time. I think our diocese is doing an excellent job.

Great story about your incredible journey in Guatemala and Mexico. I’d love to hear more about it. Muchas gracias! Bonnie