When is a Book not a Book?

This year, General Convention began to redefine the Book of Common Prayer. I mentioned this development in my recap of General Convention on July 12. But exactly what happened, and why does it matter?

The first thing to understand is that the Book of Common Prayer is a vital symbol of the unity of the church. When the first BCP was developed by Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer in 1549, it demonstrated the hope that the Protestant and Catholic wings of the Church of England could end the conflicts of the Reformation by praying together. It was also the first time the people of England could worship in their own language, participating fully and understanding the prayers and readings. This dedication to praying in a way that people can understand and share is a core commitment of our church – which is why the Book of Common Prayer has often been revised to reflect evolving language and culture.

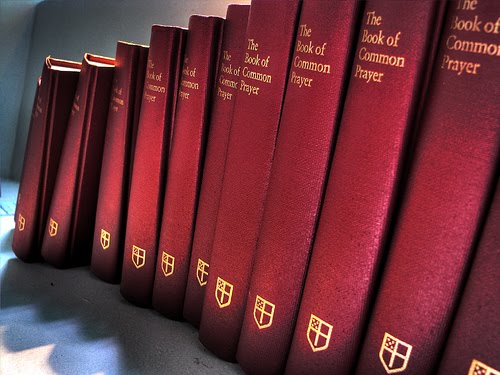

In the Episcopal Church, the Book of Common Prayer has been regularly updated since our first prayer book in 1789. It was last revised in 1979, in the midst of the liturgical renewal movement (of which the Vatican II conference in the Roman Catholic Church was one example). The 1979 prayer book reflected a rediscovery of the centrality of Eucharist as the basic act of Sunday worship, and the sacrament of baptism as the foundation of Christian belonging and ministry.

Currently, there is a growing movement to revise the BCP once more, to update some language, allow more gender-inclusive language, and provide for a wider variety of worship styles (including those appropriate to the 16 non-US countries that are represented in the Episcopal Church). Yet there is also hesitation to update the book, and I too approach the idea of prayer book revision with some caution, because I want to make sure that the essential theology of our church as expressed in the Creeds does not change. (I do not believe the bishops of our church would ever approve any change to our creedal theology.) The deepest opposition to revision, however, arises among conservatives, led by the so-called Communion Partner bishops, who oppose same-sex marriage as a rite of the church, and do not want to see it added to the prayer book.

The 2018 General Convention responded to this conflict by agreeing to “memorialize” the 1979 BCP. What does it mean to “memorialize” a book? Well, your guess is as good as mine, since the term was nowhere defined in the resolution. But most people agree that the intent of the resolution was to agree that the 1979 prayer book will always be recognized as either THE or AN official BCP, while allowing the development of new worship forms that will be available in other formats. That compromise satisfies conservatives, who can read the definition in the published 1979 BCP that marriage is a covenant between one man and one woman. It also reassures others that continued development of new language for worship can continue. Some new language for worship is contained in other books such as Enriching Our Worship, which is an Episcopal form of worship that has experimental status and is not part of the Book of Common Prayer, but has been authorized for use by a majority of bishops, including me. There are also some experimental non-BCP rites with gender-inclusive language for humans (retaining the official Trinitarian language of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit), which are published online and authorized for use by many bishops, including me.

With some minor exceptions, changing the official Book of Common Prayer requires the change to be approved in identical form by two successive General Conventions. “Memorializing” the 1979 prayer book seems to mean that while other rites may be developed and be available online or in supplemental books, those rites will not have official prayer book status, and the 1979 book will be immortal and unchanging.

However, the fact remains that in 2018, same-sex marriage was approved by Convention as a “trial rite.” A trial rite, if approved by two successive General Conventions, can achieve Book of Common Prayer status. Several bishops have committed to bring the same-sex marriage rite forward for a first reading for prayer book status at Convention in 2024, meaning that the rite could receive final approval by 2027, even if the published-on-paper 1979 prayer book stays identical to the one we have today.

Why is this important, if the familiar red 1979 book stays in your pew? Because when clergy are ordained, they take a vow to conform to the “doctrine, discipline, and worship” of the Episcopal Church, including the worship of the Book of Common Prayer. The substantive change that the 2022 General Convention made was to re-envision the prayer book as no longer a bound and published book. If passed in identical form by the 2024 General Convention, the Book of Common Prayer will be defined, not as the familiar red book you see in your pew, but as “those liturgical forms and other texts authorized by the General Convention.” The challenge for some is that if rites that are not part of the published and bound red book, but which have gone through the full approval process and are available online or in supplemental books, have official prayer book status, they become part of the doctrine, discipline, and worship of the church. If that happens, bishops and clergy who hold the view that marriage is between one man and one woman may be faced with a challenge to their ordination vows to conform to the doctrine, discipline, and worship of the Episcopal Church.

When one of the Communion Partner bishops pointed out this challenge during the House of Bishops’ discussion on BCP revision at Convention, Bishop Michael Hunn of the Diocese of the Rio Grande made an excellent observation. When we clergy vow to conform to the doctrine, discipline, and worship of the Episcopal Church, he said, we are not conforming to the doctrine, discipline, and worship as they existed on the day we were ordained. We are conforming to the doctrine, discipline, and worship of a church that has defined processes for change and growth. The changes that occur during our ordained life, which are agreed to by the church’s processes, are part of the vows clergy made to a church that does intentionally change and grow.

It remains to be seen whether the redefinition of the Book of Common Prayer will pass in identical form on the second reading in 2024, and become part of the constitution of the Episcopal Church. And it remains to be seen what effects that redefinition will have on the church, if it does happen. For me, I welcome the change in definition, and believe it is an appropriate response to new ways of communicating, sharing information, and respecting the dignity of every human being.